As a healthcare professional with an interest in the environment I strive to consider environmental issues in day-to-day work. Having recently begun to support the antimicrobial agenda within my area I am keen to explore a link between the two agendas as I develop my antimicrobial stewardship knowledge.

The bigger picture: We exist within our environment; through the food  we eat, air we breathe, water we drink plus the sights and sounds we experience, every minute of our lives. Not to mention the bacteria we interact with constantly. A degradation of our environment is detrimental to health and will also reduce our ability to respond as a healthcare system. Without intervention by 2045, the UK is expected to run out of sufficient drinking water, with heatwaves becoming the norm. By 2050, it is expected that what are currently safe hospitals will be sited in flood zones, as well as thousands of homes in places such as Cardiff, Blackpool, Bristol, Kent, London and Suffolk1. Air pollution is the biggest environmental threat to health in the UK, with between 28,000 and 36,000 deaths a year attributed to long-term exposure. There is strong evidence that air pollution causes the development of coronary heart disease, stroke, respiratory disease and lung cancer, and exacerbates asthma.2

we eat, air we breathe, water we drink plus the sights and sounds we experience, every minute of our lives. Not to mention the bacteria we interact with constantly. A degradation of our environment is detrimental to health and will also reduce our ability to respond as a healthcare system. Without intervention by 2045, the UK is expected to run out of sufficient drinking water, with heatwaves becoming the norm. By 2050, it is expected that what are currently safe hospitals will be sited in flood zones, as well as thousands of homes in places such as Cardiff, Blackpool, Bristol, Kent, London and Suffolk1. Air pollution is the biggest environmental threat to health in the UK, with between 28,000 and 36,000 deaths a year attributed to long-term exposure. There is strong evidence that air pollution causes the development of coronary heart disease, stroke, respiratory disease and lung cancer, and exacerbates asthma.2

Awareness within healthcare is rapidly increasing in how delivering healthcare unfortunately can have negative environmental impacts. The challenge to healthcare is how to continue to improve the health of our populations whilst minimising the risk of harm to this and future generations through climate change and environmental degradation. Interest groups such as Greener Practice and national drives including NHS net zero and Greener NHS Community are beginning to create change within healthcare but ultimately this is an agenda that requires all our efforts immediately.

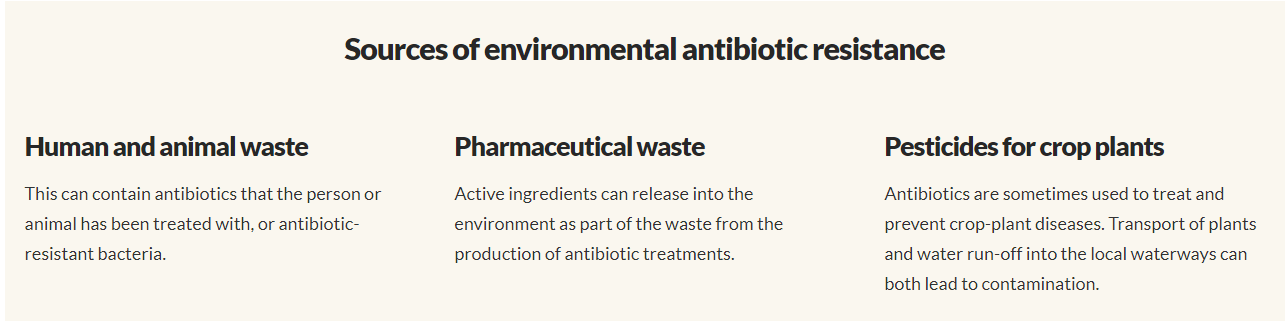

Antimicrobial resistance and the presence of antimicrobials within the environment is one element of how human activity can cause environmental issues which impact on human health. This contamination can cause the development of antibiotic resistance and the spread of existing resistant organisms. These drugs and bacteria are often found in the waterways and soil, but we know little about the scale of the risk they pose or their modes of transmission.3 Resistant bacteria may spread through food, animals, human contact, travel and healthcare facilities as outlined in this infographic from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Medications including antibiotics have a life cycle. From extraction of resources, production, distribution, administration to elimination or disposal. Each one of these steps interacts with our environment such as air pollution, use of natural resources (such as water, land, trees or fossil fuels) or direct disposal into our environment. Medications in general make up 25% of the NHS carbon footprint6 partly due to this life cycle. There are opportunities during this whole process and others for antibiotics to enter our environment (see below3). Antibiotics reach the environment via excretions (urine and faeces) from humans and domestic animals, through improper disposal and/or handling of unused drugs, through direct environmental contamination in aquaculture or plant production, and via waste streams from the production of antibiotics. Undoubtedly, the most widespread emissions, and quite plausibly the largest proportion of released antibiotics, are the result of use and excretion4. York University undertook a global study of 14 commonly used antibiotics in rivers in 72 countries across six continents and found antibiotics at 65% of the sites monitored including the river Thames7. Antibiotics have been detected in water around both built up and rural areas of Scotland and laboratory studies have demonstrated the ability of ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin to inhibit growth of photosynthesising bacteria8.

It should be noted AMR is a global problem and that our use of them can impact others in the world. Owing to low production costs, China and India have become the world’s largest producers of antibiotics. Insufficient waste management and excessive emissions of antibiotic residues from manufacturing have been reported in those countries, as well as in other regions of the world4. Climate change and resistant bacteria do not recognise countries or boundaries. We should strive to ensure our actions do not affect others en-route to ultimately affecting ourselves.

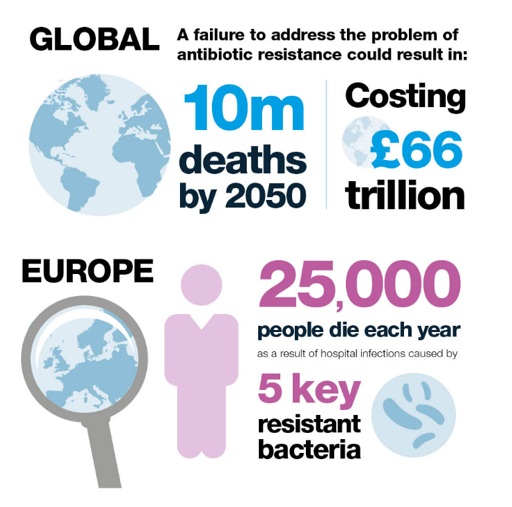

Failure to control antimicrobial resistance is predicted to lead to 10m global deaths a year by 2050 and currently 25,000 people in Europe die each year as a result of infections caused by 5 key resistant bacteria5. COVID-19 has given us a stark insight of the implications of an emerging infection we had limited ability to treat.

A balanced view: As troubling as the prospect of AMR is and links between our use of them and resistance, this should be balanced against the patient impacts of an untreated or poorly managed infection. In addition to patient benefits, preventing and managing infections can reduce further healthcare needs of a patient that result from their care escalating to admissions. The further care escalates the higher the environmental impact is likely to be from supporting them to better health.

What can we do?

Evidently the issue of AMR is larger than just healthcare such as manufacturing regulation, waste-water management and non-human routes of environmental contamination. But we can all play our part for health and the environment today and the future. When looking for improvement through an environmental lens two sustainable quality improvement principles are key. Firstly can activity be reduced, and secondly, where activity is necessary can the impact on the environment be reduced across the lifecycle. The antimicrobial stewardship principles can be applied in this manner.

Reducing Activity

Reducing Activity

Prevention of infections – Preventing infections is key to reducing patient harm and the need for acute antibiotic prescribing, whether this is lifestyle measures for UTI prevention or wider prevention of HCAIs occurring or being transmitted.

Diagnosing bacterial infection – COVID-19 may have increased people's understanding of viral infections as apposed to bacterial infections. Along with appropriate diagnoses this can aid the reduction of prescribing antibiotics for viral infections. Restarting routine audits post pandemic can aid review of the appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing.

Reducing over prescribing – In 2018 PHE reported at least 20% of all antibiotics prescribed in primary care in England are inappropriate9. Approximately 75% of antimicrobial prescribing is by general practice highlighting the scope for reducing antibiotic prescribing and the key role primary care can play. Nationally the target for antibiotic prescribing levels has been reduced further in 2021 adding expectation that prescribing levels can be remain lower post pandemic. Strategies such as delayed prescriptions, decision aids and patient information leaflets readily available may assist.

Appropriate management to reduce admissions or treatment failure – NICE prescribing guidelines for infections are easily accessible through the SWYAPC website. Ensuring prescribing is in line with guidance will optimise the management of infections and reduce the risk of resistance. Appropriate allergy histories can also reduce the risk of harm and ensure prescribing of the most appropriate antibiotic.

Reducing Environmental Impact

Reducing Environmental Impact

Patient education – Something we can all do is to re-enforce key messages at patient contacts such as understanding of expected timescales for recovery, to complete the full course, not to share antibiotics and appropriate disposal.

Waste management – Although well known by health professionals that all medications within primary care should be disposed of through pharmacy, patients may dispose of medicines in their bins, toilets or sinks which can lead to antibiotics being present within their environment. Advising on returning unused antibiotics to a pharmacy for disposal should complement all antibiotic prescriptions and supply. The end of this blog contains some national post it notes that can help with promotion of these messages.

Greener NHS – National work is ongoing to reduce the general environmental impact of medicines, improvements in procurement, distribution and recycling are being developed.

More detailed resources to implement the above can be found in websites such as the TARGET antibiotics, Antibiotic Guardian, Keep Antibiotics Working and HEE.

It seems although the exact impacts antibiotics within the environment have on humans is not fully known, the antimicrobial and environmental agendas do link together and both can benefit from joined up thinking especially through patient awareness of the link. The environment may be a key driver for some patients to change behaviours. It would be great if prescribers could continue to feedback to their pharmacy teams on how these agendas can be supported.